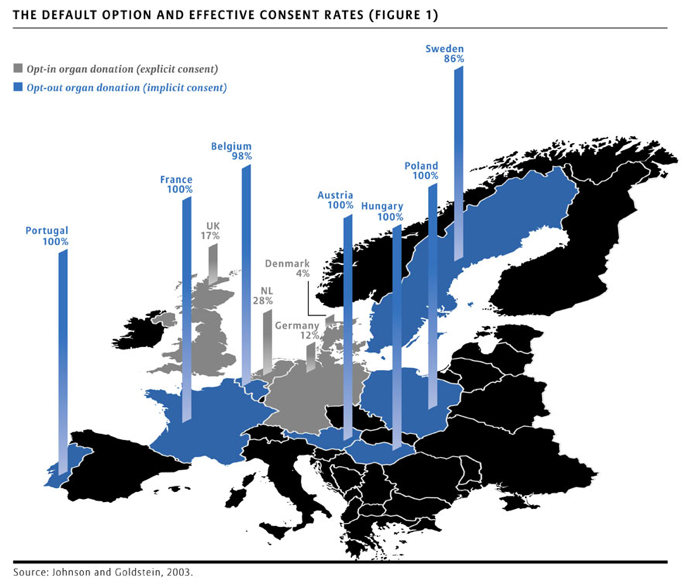

The substantial effect that the default position can have on people’s choices is a classic finding of behavioural economics. This finding has been famously applied to address the problem of the lack of organ donors in the UK. The UK has an ‘opt-in’ donor system – you have to register to be a donor – and like Denmark, Germany and the Netherlands, struggles to get a high percentage of the population registered. Other countries like Belgium, Austria and France, have an ‘opt-out’ system, that is, you have to register not to be a donor. In those countries, at least 90%, and even 100% of the adult population are registered as donors. A very simple difference in the default position appears to cause a dramatic difference in registered donors. Ireland is planning to move to the opt-out system. For the first time, it will be presumed that the deceased person had consented to donate major organs, including kidneys, heart, lungs and liver. Think about this policy in terms of the FORGOOD framework.

The below interpretations of the seven considerations are suggestions and different people will think of these differently.